According to the classic Dictionary of Modern English Usage by H. W. Fowler. emergence and emergency despite their common origin “are now completely differentiated, emergence meaning emerging or coming into notice, and emergency meaning a juncture that has arisen, especially one that calls for prompt measures”. In our actual world, however, they currently seem inextricably linked and feeding one another.

Emerging phenomena are causing emergencies in all fields and requiring consequent choices. In many – maybe all – cases, these emergencies however were all but unforeseen. The scientific community at large has for a long time tried to warn the public opinion about the risks arising from our model of economic development. Loss of biodiversity, abuse of antibiotics, industrial production of meat and vegetables, overuse of fossil fuels and subsequent climate change, have not only impacted the environment but now threaten the human population as well, as many predicted. And relying on centralized forms of energy production favors political and strategical use of energy. Even the current war in Europe is fought not only on the terrain and in the propaganda, but food and energy are variously weaponized.

These words were associated with music before. The very concept of “emerging” artists has long been used in press releases and articles: emerging, it was implied, from a sort of underground or nursery, acquiring a profile on the horizon seen by the public through the choices of programmers and critics. But now we are all trying to emerge while still dealing with the emergencies that continuously arise, while for “emerging” musicians the path to the acquisition of a higher profile seems even more arduous and complex than before: a situation, as it were, of permanent emergency.

from the first emergencies, the first notes

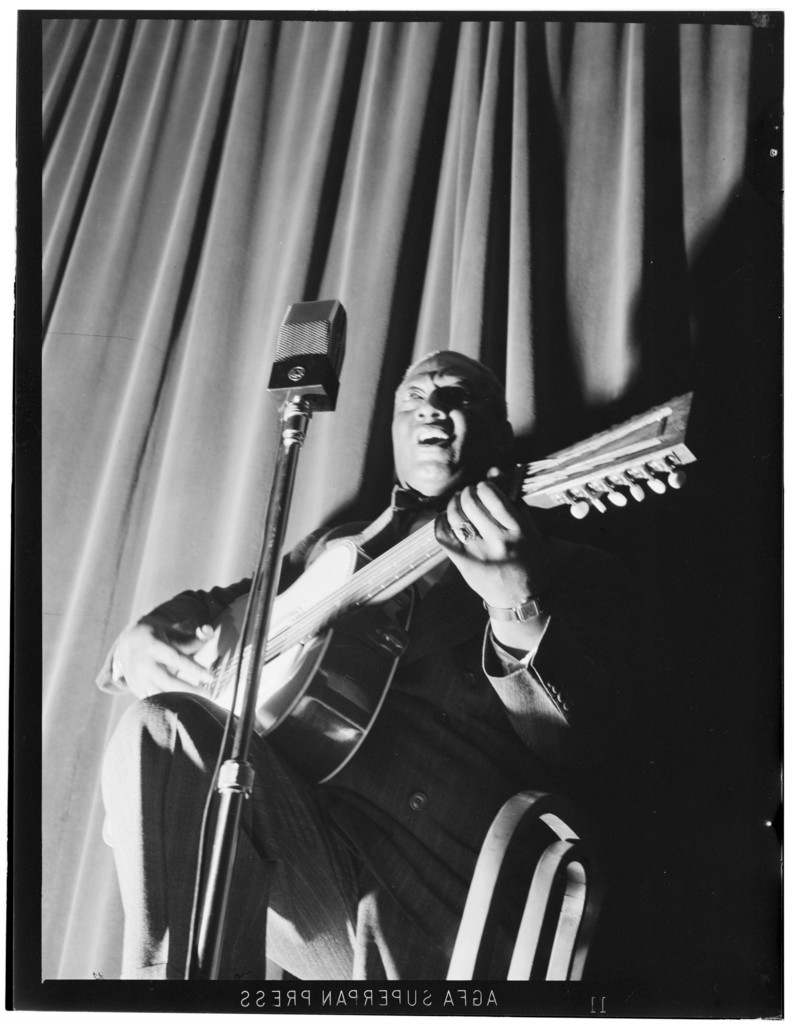

Jazz – the music spurred by the African experience in the Americas, and its musicians – has in many ways lived historically on the fine line between emergence and emergency. It certainly did arise from a situation of emergency: it came to represent on the social and cultural scene the expression of the African diasporic community of the United States of America, through the artistry of creators who used the very few available means – cheap guitars in the Mississippi Delta, discarded instruments from the Civil War in New Orleans – to create a new language that changed the world’s popular musics. It announced the break into visibility, the appropriation of instruments, techniques, of the public sphere and of the market. It was an act of self-autentication. If you’re invisible, like Ellison’s Invisible Man, how do you make your presence felt? With sound.

Its emergence slowly brought to a wider notice in the USA and in the rest of the world the achievements and the aspirations of the specific community created by one of the greatest social upheavals of history, an event that established in fact the financial basis of modernity: the slave trade that in the course of three centuries forcibly displaced millions from their homes and families in Africa bringing them to death in the travel or finally to the unbearable conditions of slavery on the American shores.

It is difficult, and also quite convenient, for Europeans to gloss over this fact, that needs to constantly be reminded, as for centuries and even today displaced people of African origin are constantly reminded of the hue of their skin. Theirs is a situation full of potential emergencies, and the very lightness, humor and danceability of the music was a celebration of life in face of them. A darker feeling mostly pervaded the blues, where emergencies in everyday life feature frequently: pests, floods, lack of means: Bessie Smith sang about the flood in High Water Blues, Leadbelly told the story of the beetle devastating cotton fields in Boll Weevil Blues, and financial dire straits appear in endless blues songs.

the emergence of jazz and emergence in jazz

It was a contrasted emergence, to be sure. In fact it was never permanent, and had to continually change shape. Languages, techniques, forms, were co-opted in the entertainment business, and jazz kept living in a borderline area: hidden from the view of the great public, but at the same time well present in the major musical genres of commercial success, from the song to the musical theater, from film to recorded music.

The emergence of jazz and the emergence in jazz are of course two related but different questions. In order to emerge in jazz, musicians had to deal with several sets of “doorkeepers” in a manner similar to painters in the art world. Critics, journalists, historians, DJ and radio programmers, record producers, A&R men, club owners and promoters of live events (concerts and festivals) all had their say in the careers of musicians. Many times these roles were confused or switched in a maze of conflict of interests that led to intellectual dishonesty if not to corruption. Many musicians did not develop a strategy that allowed them to navigate the situation, made even more complicated by the ever present color line. Louis Armstrong was brutal in his memories: “We niggers have to choose a white master, and the master will protect you from other whites.” Musicians like Jelly Roll Morton, Sidney Bechet, Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus were deemed “problematic”, “unstable”, accused of having an inflated ego, and easily labeled as psychologically disturbed. Not that the balancing act required in order to build a career in jazz could not produce the conditions for manic episodes, or for abuse of substances. Some of them through steel determination managed to keep working and recording; some of them – Herbie Nichols a major example – were ground into dust by the machinery, and succumbed, or left music. For black women of course the hurdles were even higher. Only now Mary Lou Williams is beginning to occupy in jazz history her major, rightful place. But the redressing of this history has only just begun.

In order to emerge in jazz, musicians had to deal with several sets of “doorkeepers”. At the same the emergence of jazz into the popular culture landscape was far from linear.

At the same the emergence of jazz into the popular culture landscape was far from linear. For the general public Paul Whiteman (what an irony in the name) represented jazz. He was an excellent and sensitive arranger and organizer, and gained musical respect commissioning Rhapsody in Blue to George Gershwin, as well as featuring in his band in the late 20’ a series of hot improvisers like Bix Beiderbecke and his circle of Chicagoan musicians. These name were known only to a selected public, and were certainly not the reason of the band’s popular success. Even in Harlem, the hotbed of African American culture and music, jazz elicited a limited enthusiasm, if not downright hostility, from the leading lights of the Harlem Renaissance. While thanks to Fletcher Henderson and Duke Ellington the language of the big band was taking shape with a novel integration between writing and improvising, jazz was relegated to the background of cabaret shows. And stride piano, the dynamic style that articulated the rhythmic thrust of ragtime in a most modernistic way, was the emergency tool, the soundtrack of survival, when “rent parties” became an effective way for families to pool together money for the rent and manage relations with landlords. Duke Ellington fondly remembered major figures, legendary characters of that scene, that became for him, a greenhorn from Washington, a sort of finishing school. And being able to reply, compete, sustain a dialogue in that context was certainly a way to emerge among peers: a mechanism that found further refining in the swing era with the birth of the jam session.

jazz, in touch with History

The crash of Wall Street almost killed the entertainment industry and many jazz musicians disappeared from view. Emergency meant menial labor, or at best low-pay music jobs: barn dances, tent shows, vaudeville. Some emigrated to Europe or elsewhere in search of greener pastures. Louis Armstrong answered masterfully to the crisis, transforming it in fact into a springboard for his career as a singer, expanding the jazz repertory to cover all contemporary popular songs, not only the ‘race’ songs, and in fact founding the current concept of reworking personal expression into pop songs – songs that after the 1920 and Alexander’s Ragtime Band were mostly jazz inspired anyway.

The end of that emergency when in 1935 the end of the Depression came into sight allowed the emergence into the mainstream of festive music and dancing styles created in the Black culture: Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw, Dorsey Brothers and Glenn Miller, Fred Astaire’s movies, and jitterbugs. In their communities – and never entering the top tier of fees paid – the Black bands reached a certain amount of social prestige and financial stability.

If there’s a point where emergence and emergency collided was surely the contemporary story of Roma musician Django Reinhardt who managed to emerge as a leader of a new jazz style despite the loss of mobility in two fingers of the left hand due to injuries sustained in the fire of his caravan several years before. He had achieved early success as a dance band banjoist but the fire seemed destined to put an end to his musical career had he not managed in the mid-thirties to transform a liability into the basis of a new style.

Fascism in Italy and later Nazism in Germany would actively try to block the emergence of African-American inspired music while during wartime in the USA the big bands found themselves in another emergency, the emptying of ranks due to musicians being drafted into the army. The void was filled, surprisingly for the general public, by the amazing rise of the All-Girls swing band, the most celebrated example being The International Sweethearts of Rhythm, a big band that was not only all female but racially integrated.

resurrections et re-emergences of jazz

Post-war the panorama of popular music was totally changed, and its industry restructured, by several key technological innovations. Reel-to-reel tape recorders allowed more fidelity and at the same time opened the way to editing and multi-tracking; vinyl further differentiated the formats between the song and accepted classic compositions; the 1947 invention of the transistor revolutionized radio listening creating the space for teenagers to listen to their own songs away from the family and discover the local rhythm’n’blues stations. The right collection society ASCAP saw its supremacy challenged by the newcomer Broadcast Music Incorporated: the days of Tin Pan Alley were over. Jazz – as it was defined then by the canonizers – almost disappeared from the scene, saved as a niche market by a new type of listener, the suburban intellectual with his hi fi system. Jazz went to college, as a famous title proclaimed, both as a concert music and a teaching subject. Despite Schuller and the Third Stream, the leading lights of the music were however excluded. Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, not to mention Charles Mingus, kept toiling in low fees club, while Ellington’s strategy of surviving thanks to the royalties of his compositions paid off in a time when big bands gigs were few and far between. Despite eminence, emergence was contrasted and it must surely have been at least one of the reasons for Davis’ following choice of changing character of his music and his public persona.

Jazz maybe did not gain a high profile, but certainly its underground existence allowed it to always re-emerge in various forms: dance music, film soundtrack, even jingles for advertisement.

While the sounds of many jazz musicians emerged in instrumental solos enriching classic pop songs and sometimes even creating the hook that made songs famous, their names and careers were lost on the public at large, that listened to a lot of jazz without even realizing it; not only in the solos, but in arrangement and composition techniques, and even innovative instrumental timbres: most of the electric instruments (electric guitar and bass, Hammond organ, Fender pianos) have been popularized first via jazz or related music.

Jazz maybe did not gain a high profile, but certainly its underground existence allowed it to always re-emerge in various forms: dance music, film soundtrack, even jingles for advertisement. Currently a new wave of musicians is inspired by several undercurrents of jazz: free and electronic experimentation, spiritual jazz of the Sixties, lounge music of the Fifties, funk jazz of the Seventies: a phenomenon that maybe began even in the Eighties when another generation of creators, faced with its own emergencies, adopted and adapted the technologies of vinyl and mixing exactly as their ancestors had used cheap guitars and discarded instruments in order to create a low-cost, high-impact new form of expression, often recycling among other things, the jazz records of the past.

Francesco Martinelli

September 2022